On this Day in 1509 a large joint naval force led by Malik Ayyaz, (Captain of the City of Diu and Commander of the Sultan of Gujarat's fleet), the Mamlûk Burji Sultanate of Egypt, the Zamorin of Calicut with support from the Turkish Ottomans, the Republic of Venice and the Republic of Ragusa were soundly defeated by a much smaller but greatly superior Portuguese fleet off the western coast of India – in view of the fortress port of Diu - east of what is now known as the Persian Gulf.

The Battle of Diu, is one of those often forgotten historical firsts – or turning points – that mark the beginning of a major chapter in history. In this case, the beginning of the Portuguese Empire's dominance of the East Indies and India for a hundred years until their loss to the Dutch beginning with the Dutch-Portuguese War of 1602.

The Portuguese are remembered these days as great explorers and traders. However in the 16th century they were known by those that opposed them as the most militarily formidable, fearsome, cruel, and bloodthirsty pirates and conquerors the world had ever known.

By 1509 their reputation was already well established. The famous “explorer” Vasco da Gama is well known affectionately by most grammar-school students in the west, as the man who in 1498 first discovered and opened the eastern trade route to India – sailing around the southern coast of Africa (The Cape of Good Hope). However most would be shocked to find out that upon his arrival in the Indian Ocean, his fleet plundered and pillaged indiscriminately – preying upon dozens of settlements on the east coast of Africa all the way to India. As soon as he reached the Indies, he immediately began to pit local Indian factions one against another in order to gain Portugal's first foothold in India. He waged war in the area around Calicut and was known to be completely heartless – granting no quarter to prisoners.

Da Gama also has the dubious honor of committing the first known acts of piracy by a westerner in the east. This particular act is an atrocity so horrible that it makes later “bloodthirsty” pirates like Blackbeard look like effeminate school boys. Da Gama's fleet seized the Arab ship Meri in the Arabian sea in 1502. This ship was loaded down with valuable silks and precious goods - which the Portuguese immediately looted. The vessel also carried over 300 Muslim passengers on their way to Mecca for the Haj(pilgrimage).

Once the ship had been picked over, Vasco da Gama ordered the passengers confined below, the hatches bolted shut, and the ship set afire. Before the Portuguese could execute this villainous act, some of the Muslim men, wise to what was unfolding, busted open the hatches, and put out the fires. They put up a valiant fight, but in the end every last man woman and child was heartlessly butchered. Da Gama spent most of the time during this carnage in his quarters - indifferent to the cries of his victims.

With his ships filled to bursting with spices and silks he set sail for home, leaving behind such a path of misery and destruction, that his name is still remembered with infamy in the East to this day.

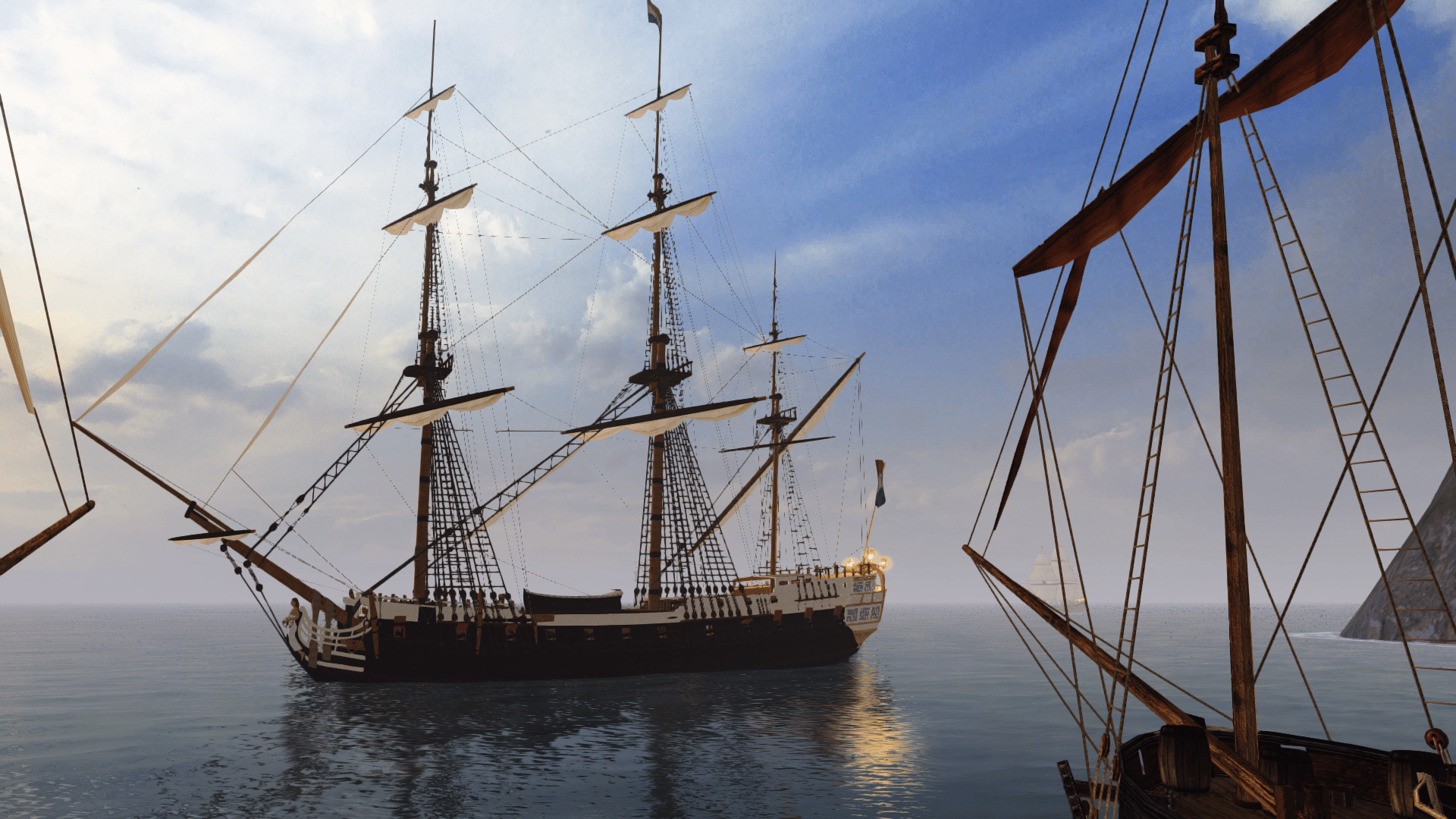

A known dread and fear of the Portuguese by the indigenous peoples of the east has survived the centuries in their narratives, poetry, and even bedtime stories. The gigantic vessels of the invaders (known as “the Black Ships” to those that regularly encountered them), were seen as unstoppable floating fortresses of doom bristling with hundreds of guns. It is with this reputation and dread in mind, that one can easily imagine the mood and fear that must have prevailed as the Captain of Diu, Malki Ayyaz hastily assembled his joint fleet of ships and men to oppose his enemy - Francisco de Almeida, Viceroy of Portuguese India.

Almeida had gone rogue. He wasn't even supposed to still be there. He should have been on a ship bound for Portugal. His replacement Afonso de Albuquerque had arrived from Lisbon. (incidentally Albuquerque is also remembered for his infamous reputation of revenge and brutal seizure of Malacca in 1511) Instead of a warm greeting and the usual “hand-over” of responsibilities, Almeida immediately threw his replacement in jail without explanation - and hastily disembarked on his long prepared and planned expedition to assault Diu.

Why? In short, this was personal. Almeida was consumed with hatred and a desire for brutal revenge against Mirocem (Amir Husain Al-Kurdi), and Malki Ayyaz, the Captain of Diu and commander of the Sultan of Gujarat's Egyptian Mameluk fleet. Less than a year earlier a force of several Portuguese ships was surprised by this fleet. During the skirmish, the greatly outnumbered Portuguese ships escaped – that is all - but one. This was not unusual, as the Portuguese carracks or “naus” towered so high out of the water, and were always so well armed and very well manned – that they were extremely difficult prizes to capture.

Malki Ayyaz concentrated all of his forces on this one single ship - surrounding it and assaulting it over and over again until Mirocem (Amir Husain Al-Kurdi) was finally able to take her. There were only nine survivors. Among the dead was the ship's (and flotilla's) commander, Laurenco de Almeida – the son of the Viceroy of India.

Dom Francisco was grief-stricken when the news of his son's death reached him. He immediately began to plan an expedition of revenge. In 1505, the King of Portugal, Manuel I, had sent twenty one large Portuguese warships (carracks) to bolster his Empire in the east. Over the course of four more years many more had arrived as well.

The fleet that the Viceroy now commanded was not the small flotilla of a few medium carracks his son had led. This was a large well armed fleet of eighteen warships. On board were at least a thousand sailors, and over 1500 heavily armored soldiers commanded by dozens of knights. In addition, four to five hundred auxiliary troops of native militia (mainly from Cochin) were aboard.

The senior military and government officials of Diu knew that Almeida was coming. They had received a letter months earlier from the Viceroy. In the letter Almeida makes his intentions very clear:

“I the Viceroy say to you, honored Meliqueaz captain of Diu, that I go with my knights to this city of yours, taking the people who were welcomed there, who in Chaul fought my people and killed a man who was called my son, and I come with hope in God of Heaven to take revenge on them and on those who assist them, and if I don't find them I will take your city, to pay for everything, and you, for the help you have done at Chaul. This I tell you, so that you are well aware that I go, as I am now on this island of Bombay, as he will tell you the one who carries this letter.[2](in Portuguese)”

The city officials of Diu made several appeals to the Viceroy to diffuse the situation, stating that the Portuguese prisoners had been well treated and fed. They also offered the prisoners return without ransom, and went even further - offering the authorization of a permanent Portuguese trading station at Diu. For most political or military arbitrators, this would have been a very attractive proposal – but not for Almeida. He ignored the letters.

As the Portuguese fleet closed upon Diu, the two naval forces could not have been more different. The contrast must have been a sight to behold. The leaders of Diu had managed to talk the local Europeans into joining them. The Venetians and Ragusans welcomed the chance to oppose the Portuguese. They had once enjoyed an almost virtual monopoly on the eastern spice and silk trade via the Red Sea and Levant ports that had received their goods overland from India. The Portuguese had changed all the rules and had completely upset the balance - with an open sea route to the riches of the Indies. The European vessels that were in Diu had not been built there nor sailed there. They had been disassembled in Egypt, brought overland to the Red Sea in pieces and reassembled there.

The Ottoman Turks and the Egyptian Mamluks hated the Portuguese as well and had been fighting them for years along the Levant and North African ports of the Mediterranean. Overall, Diu's defending forces were comprised primarily of forty or more light galley class vessels with a handful of smaller Italian naos. The Turks had six large galleys and another six medium class carracks. The Sultan's fleet was composed of around eighty low freeboard dhows and prahas. Altogether Diu was able to assemble a joint fleet of over two hundred and fifty vessels of all shapes and sizes to oppose the Portuguese. However, only twelve of these ships were of a size that might be able to challenge the larger Portuguese warships in a “ship-to-ship” fight.

The strategy of the Gujarat-Mamluk-Khozikode side was to take advantage of the harbor's natural defenses – relying on a stone fort to their rear which possessed decently sized artillery pieces to duel it out with the great Portuguese carracks.

Almeida saw that his enemies had bottled themselves up in the harbor and this was probably just what he had been hoping for. He must have been very pleased. He drew his ships into a long but tightly formed semi-circular line with broadsides facing the harbor of Diu. His fleet was composed of twelve carracks of the largest size (some of the largest warships in the world at that time). Each of these ships probably had over a hundred guns of various sizes. Although most were smaller guns made for taking out enemy sailors and soldiers on enemy ship's decks below, at least ten guns per each broadside were some of the largest and longest ranging guns available in 1500.

Each of these breech-loading “bombards” would have weighed in at two or more tons and could hurl an iron or stone ball over a foot wide - (weighing over fifty pounds each) well over a miles distance. That may not seem like much now, but in 1509 – that was “shock and awe”. The Viceroy's other six ships were caravels and medium classed naus, but still all were very well armed and swarming with heavily armored naval infantry.

Almeida gave the signal to fire and a torrent of heavy cannon-fire broke the relative silence - with hundreds of deafening reports and dozens of almost simultaneous subsequent shattering impacts. The flying projectiles devastated the fortress of Diu and the vessels of the tightly packed fleet to its front.

The harbor ships and the fort returned fire, but most of their guns couldn't accurately range the Portuguese fleet or fell short. The fort and ships that could answer, were mostly ineffective with their shot harmlessly bouncing off the heavy Portuguese hulls or missing altogether. The Portuguese continued their massive bombardment for hours sinking dozens of enemy vessels and putting most of the fort's guns out of action. Unlike Diu's defenders, the Portuguese gunners were well trained professional artillerists.

With a shifting wind towards the port becoming advantageous, Almeida gave the signal to make sail and advance upon the port. The heavy carracks mowed through the small light enemy craft like frail, dry twigs - breaking and sinking many under their great bows. The Turk and Mameluk archers loosed thousands of arrows upon their Portuguese attackers, but the shelter that the massive ships allowed the westerners and the armor that they wore, made the arrows more of a minor nuisance than a serious threat.

Hand-to-hand combat in the harbor and the debarking of heavy naval infantry and knights ashore followed. Even though the Portuguese faced many times their numbers, the battle hardened and seasoned Christians were so well trained and heavily armored, that they suffered only a handful of casualties. As a result, once the Portuguese forces were all ashore a general route of the joint Gujarat-Mamluk-Khozikode forces ensued in less than an hour of heavy fighting. Diu's defenders had fought bravely and as long as they possibly could, - but they were just simply plain outmatched in every way possible – technologically, tactically, in training, in equipment, and in capability.

The battle ended in a decisive victory for the Portuguese, with massive casualties on the Gujarat-Mamluk-Khozikode side. In the aftermath, Malik Ayyaz handed over the prisoners of Chaul, dressed and well fed just as they had said in their letters to Almeida. Among the spoils of battle were three royal flags of the Mamelûk Sultan of Cairo - sent to Portugal and still on display in the Convento de Cristo, in the town of Tomar, home of the Knights Templar. In addition, a payment of 300,000 gold xerafins, was made to the Viceroy. Also the leaders of Diu surrendered full control of the city from the Sultan to the Portuguese, but Almeida refused the offer because he thought the city would be too expensive to maintain. The Portuguese did leave a garrison behind and did set up a trading post.

With the battle over, Almeida now turned his mind to his brutal and desired revenge – the motivating factor of the campaign. The Viceroy ordered most of the men of the Sultan's fleet composed primarily of Egyptian Mameluks to be hanged, burned alive or blasted to pieces - tying them with their bellies against the muzzles of his cannon.

In an almost A.T. Mahan-like prophetic comment, Almeida mused after the battle:

"As long as you are powerful at sea, you will hold India as your own; and if you do not possess this (sea) power, little will avail you of a fortress on the shore."

Almeida had satiated his burning lust for revenge, but he would follow his son to the hereafter soon enough. Almeida released Albuquerque on his return to Bombay and transferred power of the Portuguese Indies over to him. He disembarked for Portugal in November, 1509. As in the case of so many of these intensely interesting stories of the notables of this age, he never made it home. Only a month later in December, he was killed by Khoikhoi tribesman, in what is now modern Capetown, South Africa.

This is an incredibly fascinating period in history. I find it interesting that the first major battle between east and west during the colonial era was not motivated by profit, greed, power or territorial expansion – it was to extract personal revenge – in short, “to get even”. I wonder....from that time to this, has either side ever really got even since? Hmmm.

Aaron R. Shields A.K.A. MK

For further reading I recommend:

Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Diu_(1509)

Portuguese Voyages, 1498-1663: Tales From the Age of Discovery, Edited by C.D. Ley,

Pacific Voyages: The Encyclopedia of Discovery and Exploration, Doubleday

The Mediterranean, By Ferdinand Braudel

The Great Sea, By David Abulafia (still reading this one – EXCELLENT!!!)

For pictures of the great Portuguese carracks I describe in the article, see my Flickr photo set on Carracks and Naus here: http://www.flickr.com/photos/49225014@N05/sets/72157632238978960/